“Whatsoever things are true, whatsoever modest, whatsoever just, whatsoever holy, whatsoever lovely, whatsoever of good fame, if there be any virtue, if any praise of discipline, think on these things.” Philippians 4:8

***

I was raised to fear God, and fear the world, and fear my body, and fear the condition of my soul. I was raised to fear.

The apostle’s urging to think on things pure and lovely – a gospel passage relayed so often in my household that I could recite it by heart – became a divine injunction to avoid R-rated movies, Dungeon’s & Dragons, sexually explicit material, a vast array of dangers. Any interaction with dark or perverse subject matter, I was told, opened a window for “the evil one” to infiltrate my life and tempt me away from God. My mother used the phrase “spiritual warfare” to describe this cosmic struggle for my soul.

I was a sensitive kid, eager to please and preoccupied with these powerful forces I could not see or comprehend. Journal entries kept by my mother enshrined early-childhood remarks of the following sort:

“I like God and the angels. I don’t like the devil. He makes holes in my teeth.” November, 1982. I was three.

“God has eyes all over him so he can see when we’re doing bad even if Mommy isn’t there.” September, 1983. I was four.

“I wish I’d be killed… so I can go up to heaven to live.” November, 1983. I was four.

***

My fascination with darkness and death and demons persisted. I carried it with me into adolescence. I latched onto heavy metal. I bought a black Yamaha electric guitar from a friend at school, its headstock bearing a gash where it had split in two and been inexpertly glued back together. The scar remained visible.

The guitar cost 20 dollars. On it I learned to play as many Metallica songs as my fingers could traverse. I think it was my way of asserting dominion over something wild.

To listen to James Hetfield’s growl felt like standing outside in a thunderstorm. It was powerful and untamed and I could emerge from its presence intact. My parents were not cruel in wanting to offer me a sheltered upbringing, yet I wanted to feel the storm beyond that protective awning.

The voices of all those heavy-metal singers I loved contained a power that I lacked, a power I craved – to do what? Raise my voice?

***

When I left home for college I began seeking out movies that made me uncomfortable. Magnolia. Requiem for a Dream. 21 Grams. Dancer In The Dark. I forced myself to keep my eyes open and gradually found them adjusting to the dark.

That condition you hear about in which some pregnant women stuff their mouths with soil because their bodies crave some mineral contained in the dirt? Maybe that was me. Needing to find something in the soil of those flickering images, some nourishment in the immodest, unholy and unlovely.

I felt – I knew – the world was a dangerous place. I knew this because I could feel that tumult and chaos within myself. No matter how antiseptic the backdrop of my upbringing, I could feel the germs within. I needed exposure. My awakening to the power of art involved a search for a diluted specimen of the darkness I sensed within. To survive that, I needed to learn how to commune with it, somewhere beyond judgement and fear.

I needed to place my arm in the wolf’s jaws voluntarily... and trust I would be fine.

***

I have not exhausted my fascination with shadow.

The publishing company I have founded as an adult – Tune & Fairweather – enables me to usher into the world the varieties of art that coal-fired my imagination as a younger person, and still do to this day.

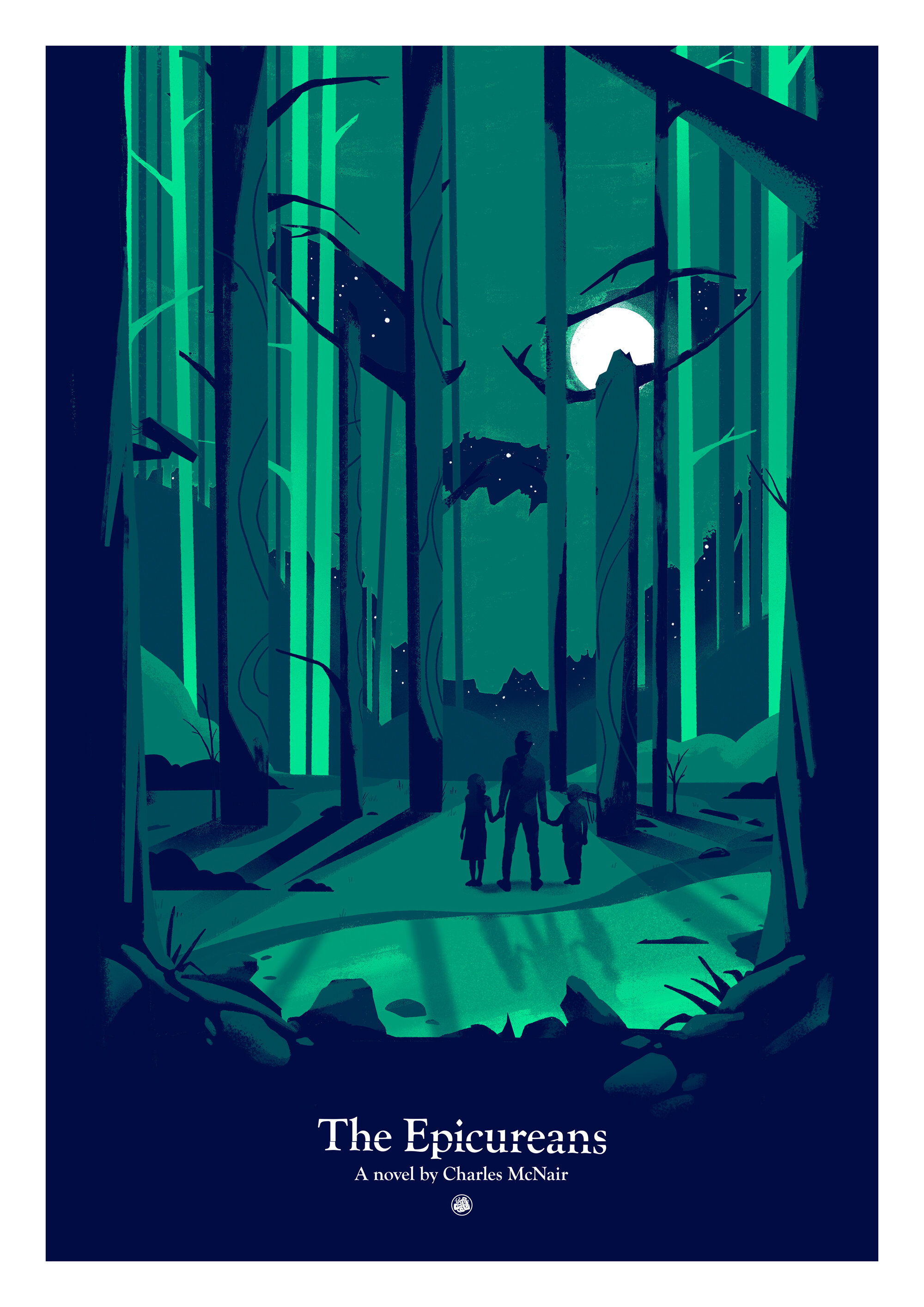

Our first novel is called The Epicureans, written by Pulitzer-nominated author Charles McNair. It’s a disturbing book full of unnatural appetites, serial murder, sex, a form of animal predation that would make David Attenborough blush. Given my childhood preoccupation with hell and demons, it probably shouldn’t be surprising that the book’s cover features depictions of demons and hellfire.

Exorcism is all about getting the demons out where you can see them.

My wife cheers me on and wishes the project every success but does not have the stomach to read the story herself. The vulnerability of young children strikes close to home. I respect her squeamishness. There’s no shame in fearing the dark. We all find a way to abide the spectre of evil in different ways. There’s no obligation to meet its gaze. Most days I avoid the news headlines.

But there’s something about the dark that I love. When you get rid of the dull haze of city lights and civilization you can look up and find bright points of light stabbing through.

The Epicureans has those underdog specks of illumination as well. You can see them clearly in the darkness, tiny specks of fire interrupting a sprawling void. The love of family, the unexpected decency of strangers, the warmth of community. Most stubbornly, perhaps, the humour that carries us through the unbearable and the morbid. Human beings are made of strong stuff. We can survive almost anything.

Even children can survive. I am still here, after all, eager to see what happens next.