What do we do with the prospect of failure as entrepreneurs? I’ve spent the last several months working on preparing for a Kickstarter campaign that is poised to run out of steam before reaching its funding goal. We’re just over 50% funded with only 5 days left on the clock. Big gulp.

The obvious temptation is self-pity: “Boo-hoo, nobody loves me. Nobody appreciates the art I’m trying to bring into the world.” This is an energy sinkhole. Self-pity is a form of narcissism. You can feel yourself crumple in on yourself – face meeting navel – when you nurse it.

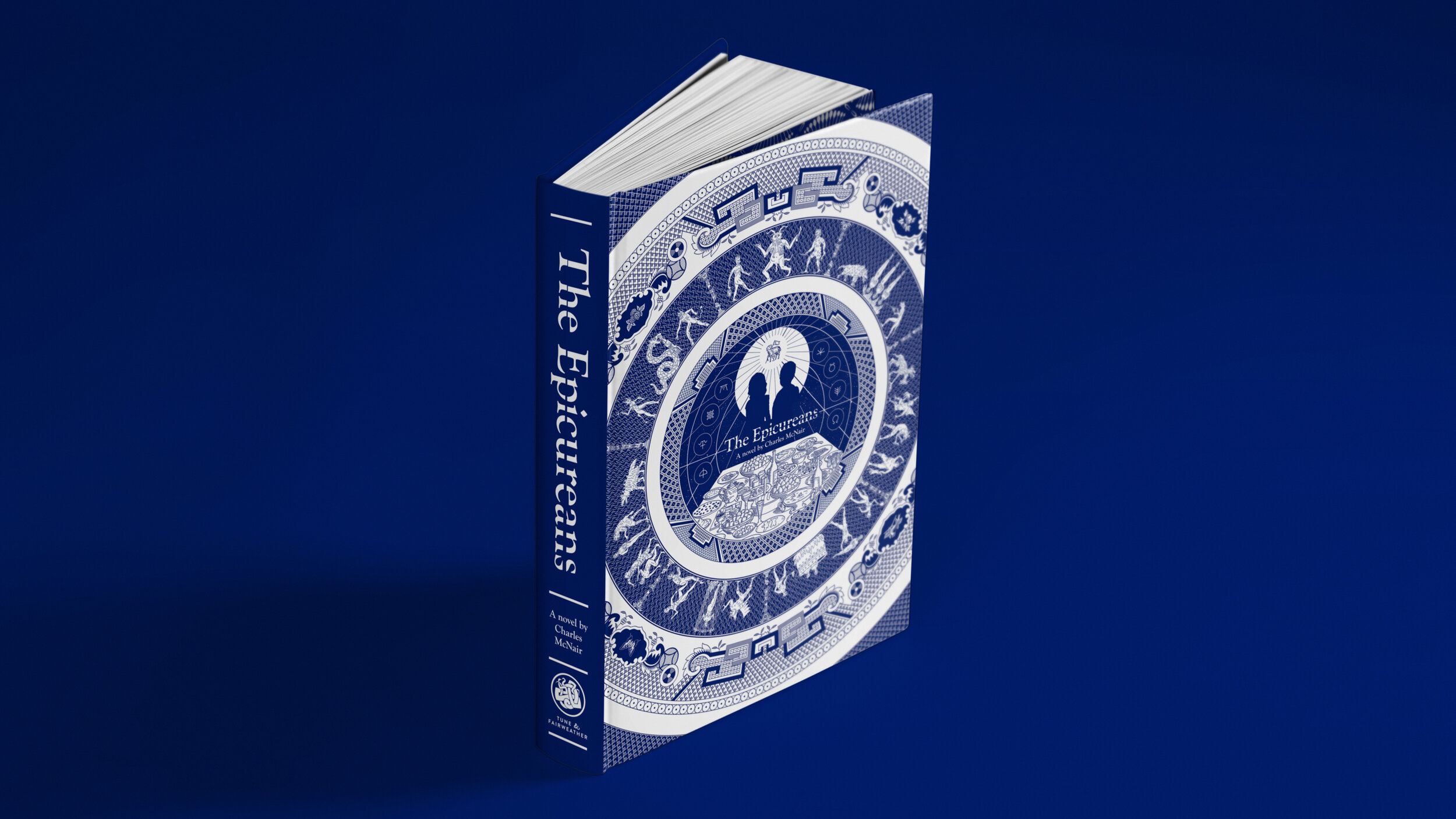

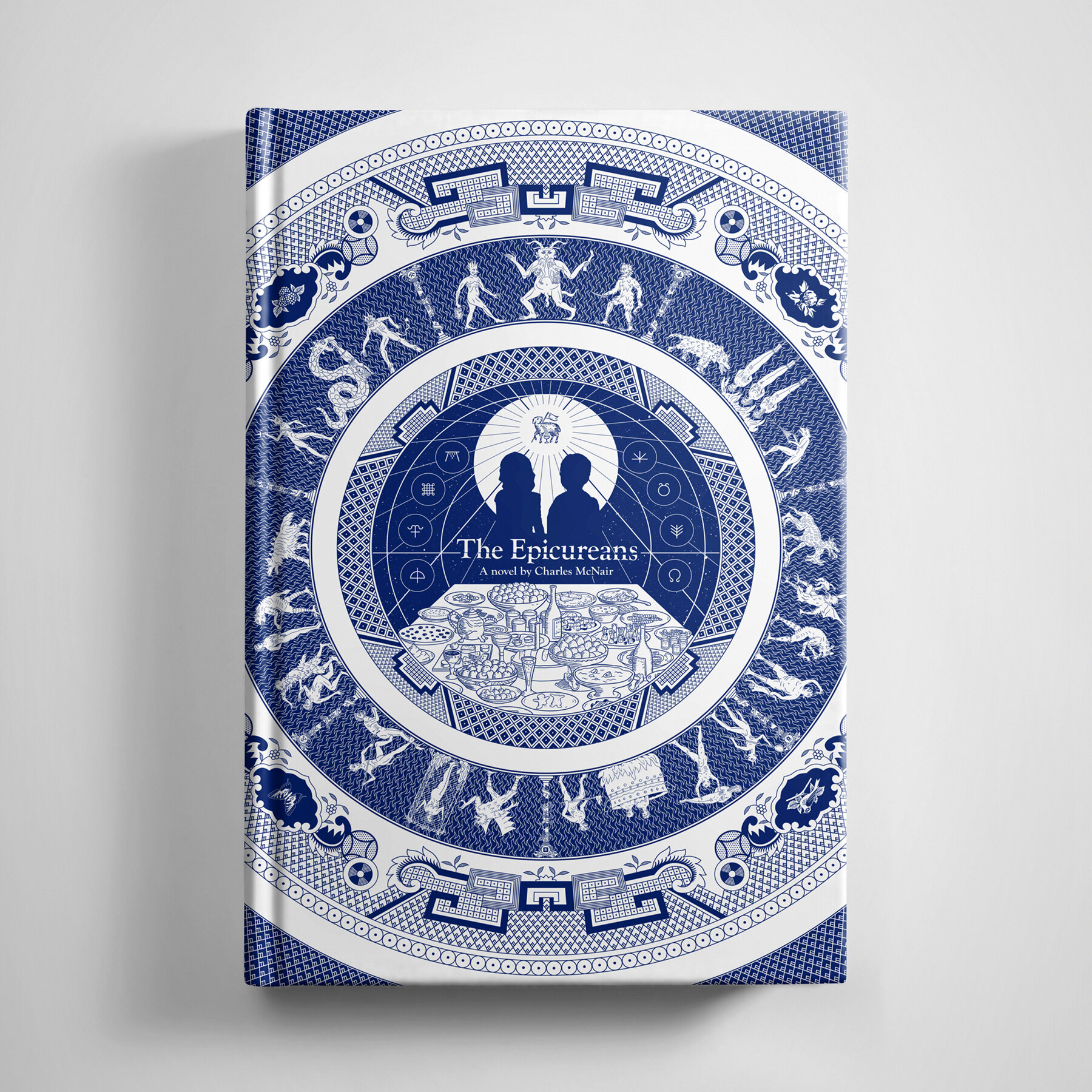

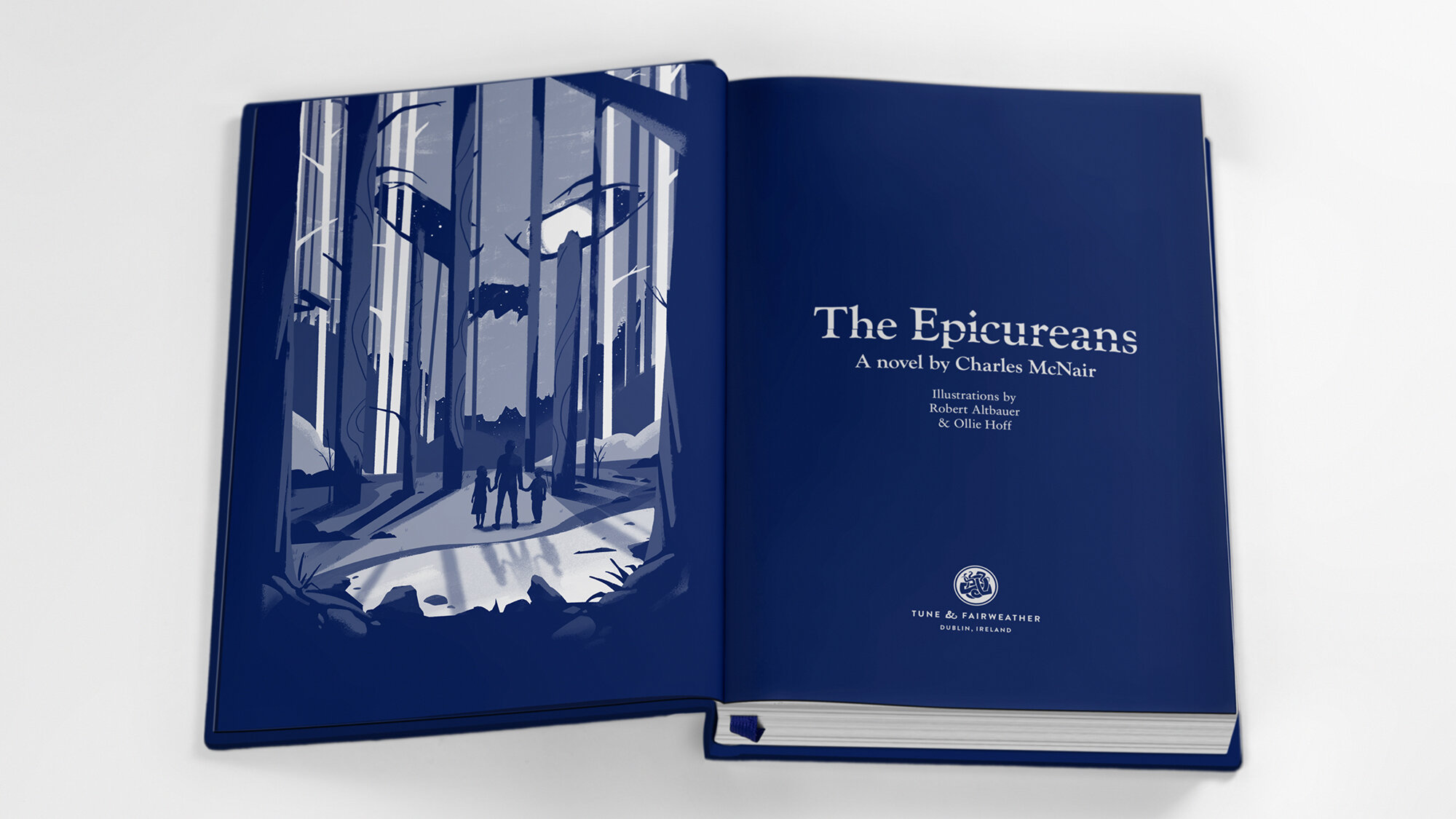

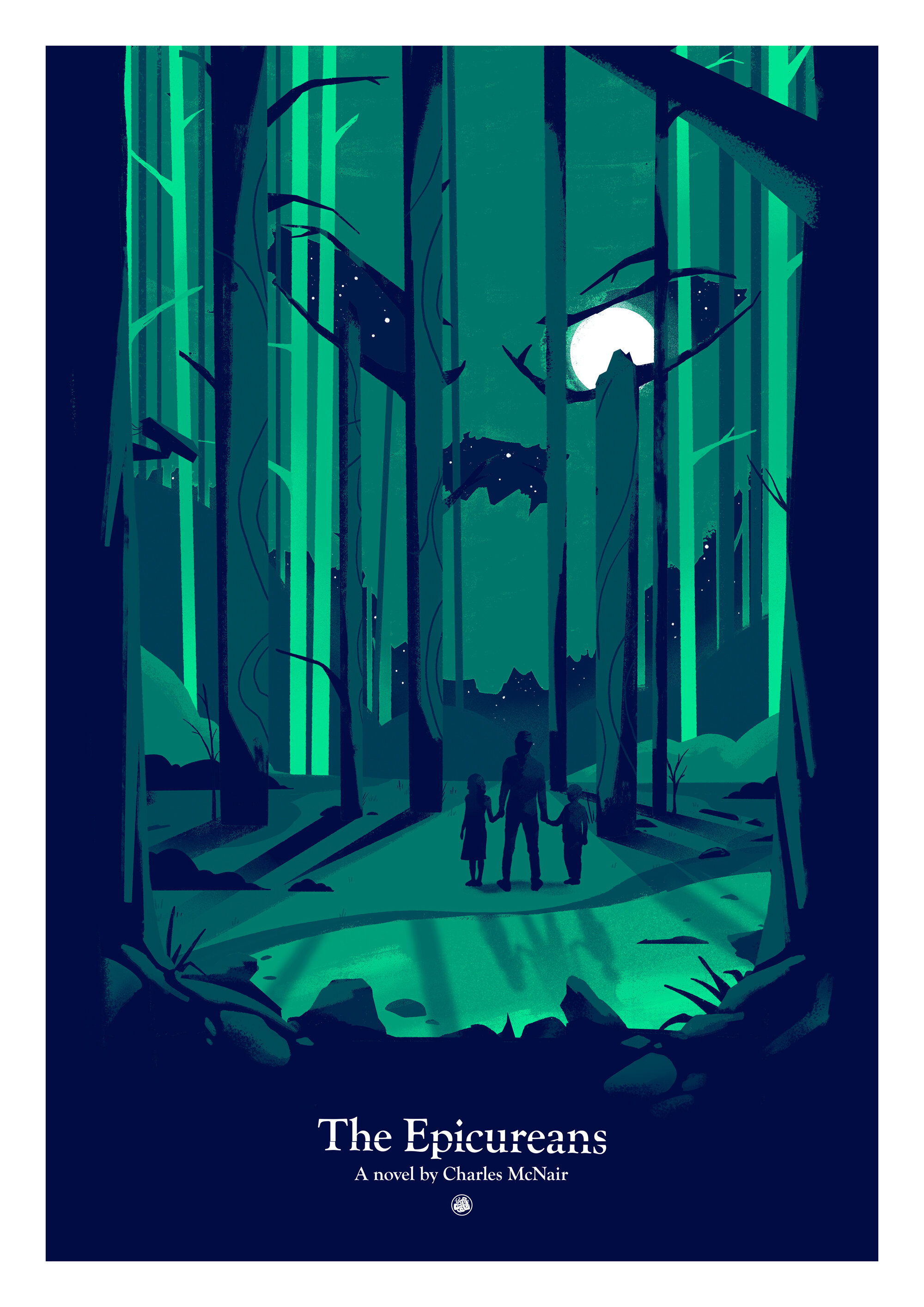

I’ve been tempted to go there. I’ve found my mind wandering to how I might word my various concession speeches (topical, eh?!) How might I spin the disappointing news or explain Tune & Fairweather’s failure to the novelist Charles McNair who entrusted us with not just designing but finding and cultivating an audience for his book?

The anti-gravity boots that have helped me resist that urge: reflecting on the words of my creativity and business mentors Elizabeth Gilbert, Brené Brown, Seth Godin, et al. The path through the bramble of any “vulnerability hangover” is to shift the focus away from oneself toward generosity. So here’s one thing I did today: I made a Spotify playlist for the 224 people who’ve already backed the Kickstarter campaign.

I’ve resolved to counter anything that has a shrinking, contractive energy. Gratitude expands, unfurls and opens us up. So I meditate on all the people who have helped along the way.

John Battle, my former colleague and craft lead at Riot Games, is a professional voice actor in his off-hours (he’s done a Super Bowl commercial FFS!). John did a reading for us of the book’s first two chapters and ignored my repeated pleas to let us pay him for his contribution. Bonkers.

My wife spent a few hours reaching out to Irish press and local libraries here in Dublin to see if they might want to boost the signal on the book’s Kickstarter campaign. I’ve had friends and even strangers share news about the campaign with their followers on social media.

The more I reflect on these acts, the more I feel my spirit expand and calm. Was it C.S. Lewis who wrote about heaven being a feast where everybody’s spoon is too long to reach their own mouth so they happily feed their neighbours and get fed in return? That visual feeds me.

If the Kickstarter fails, that’s OK. I get to follow the example of another mentor Tim Ferriss and meditate on the worst that can happen. Hint: it doesn’t involve death or dismemberment or shitting through white jeans in public. We’ll problem-solve another way to cover the printing bill. If we fumble at the goal line and miss our funding target, I get to build empathy and equanimity.

Wikipedia describes equanimity as “a state of psychological stability and composure which is undisturbed by experience of or exposure to emotions, pain, or other phenomena that may cause others to lose the balance of their mind.” I’ll order as much as the universe has in stock, thanks.

I’ll sign off with a Norman Mailer quote: “Being a real writer means being able to do the work on a bad day.” I quit my job in video-game marketing to publish (and market!) beautiful books. That’s my job. Even if I’m depressed, even if my monkey mind is trying to convince me I’m a failure or a fraud, that’s the work I get to do. And I count myself lucky to have this job. Even on a stressful or down day.