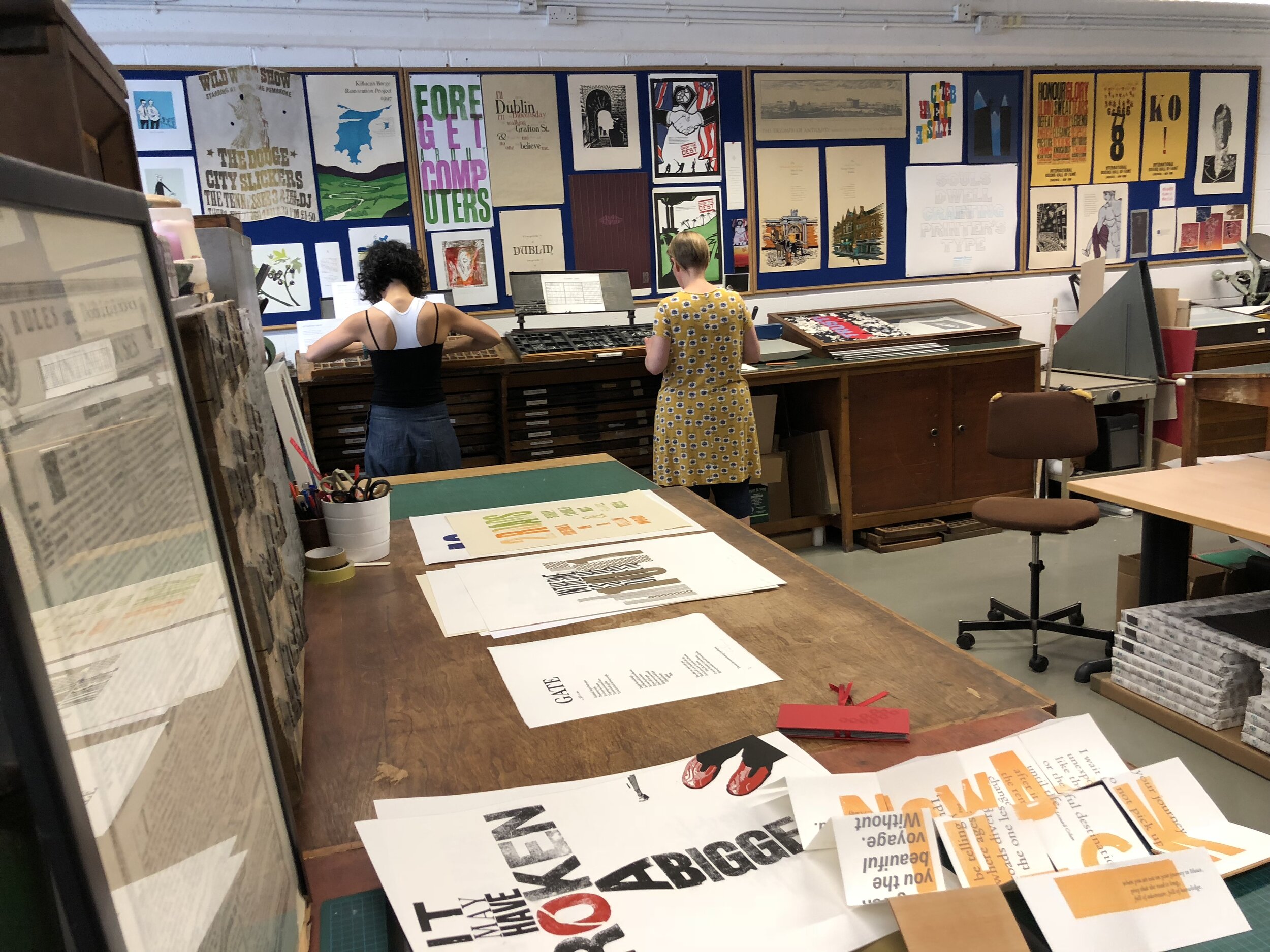

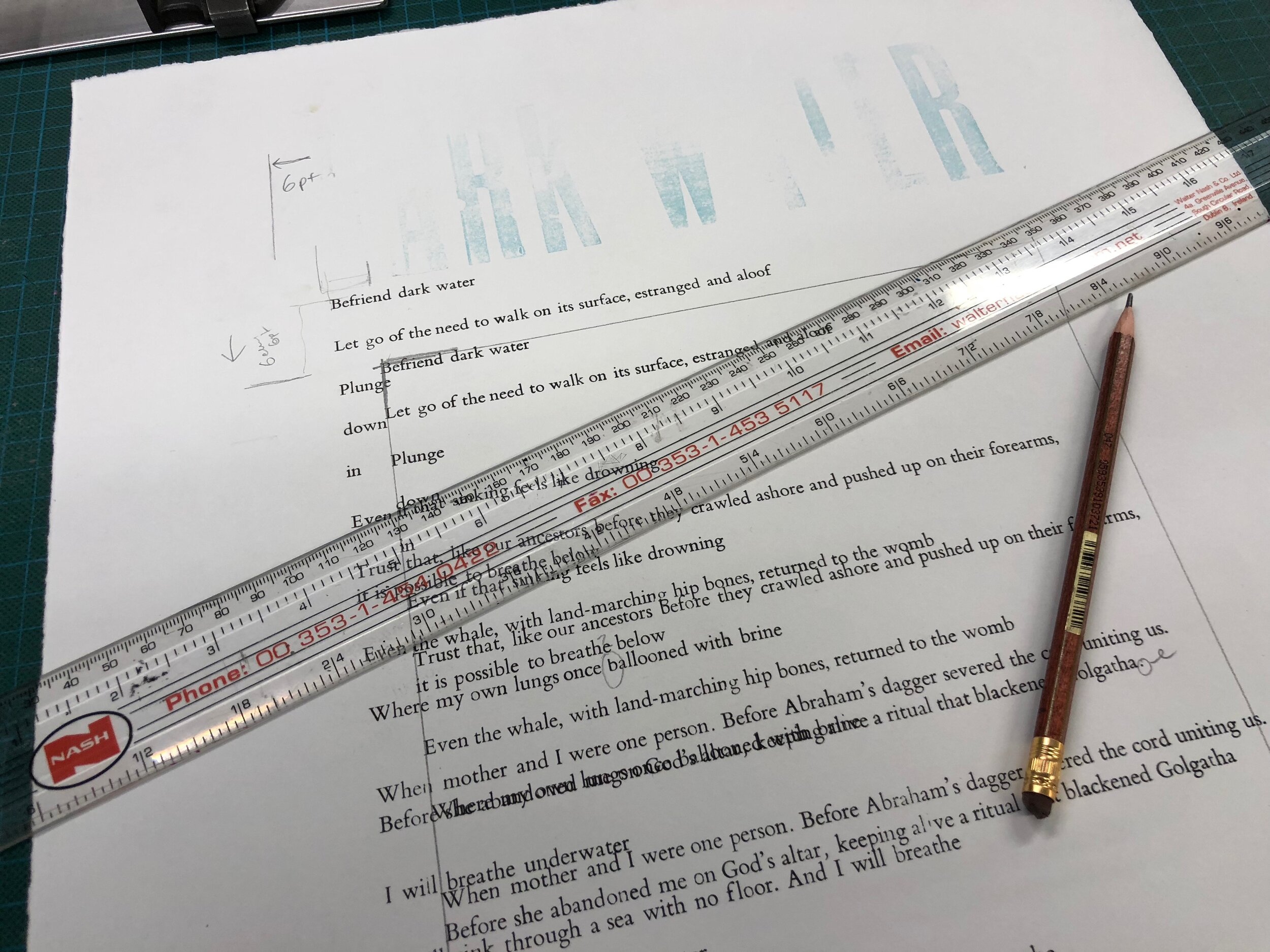

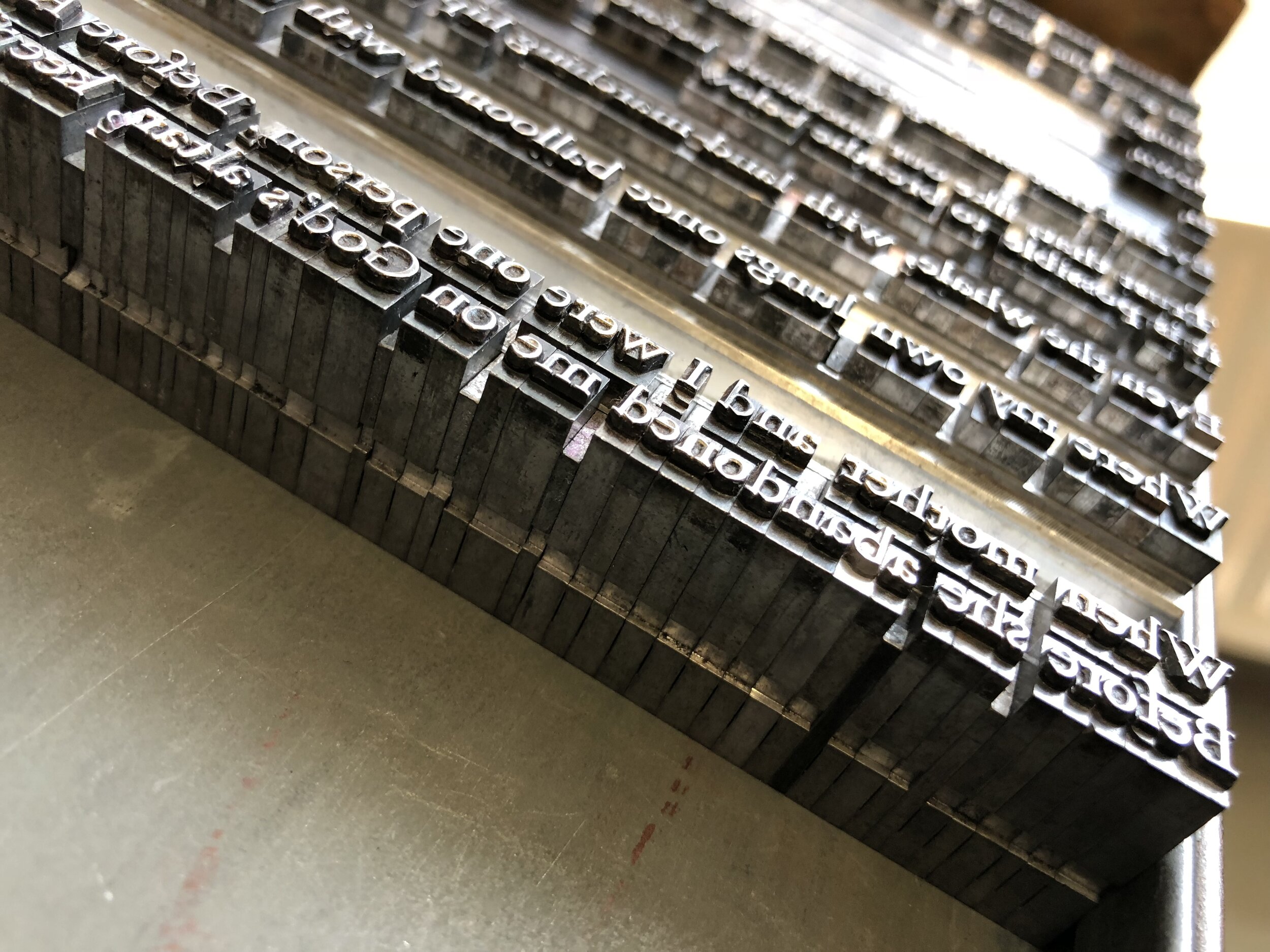

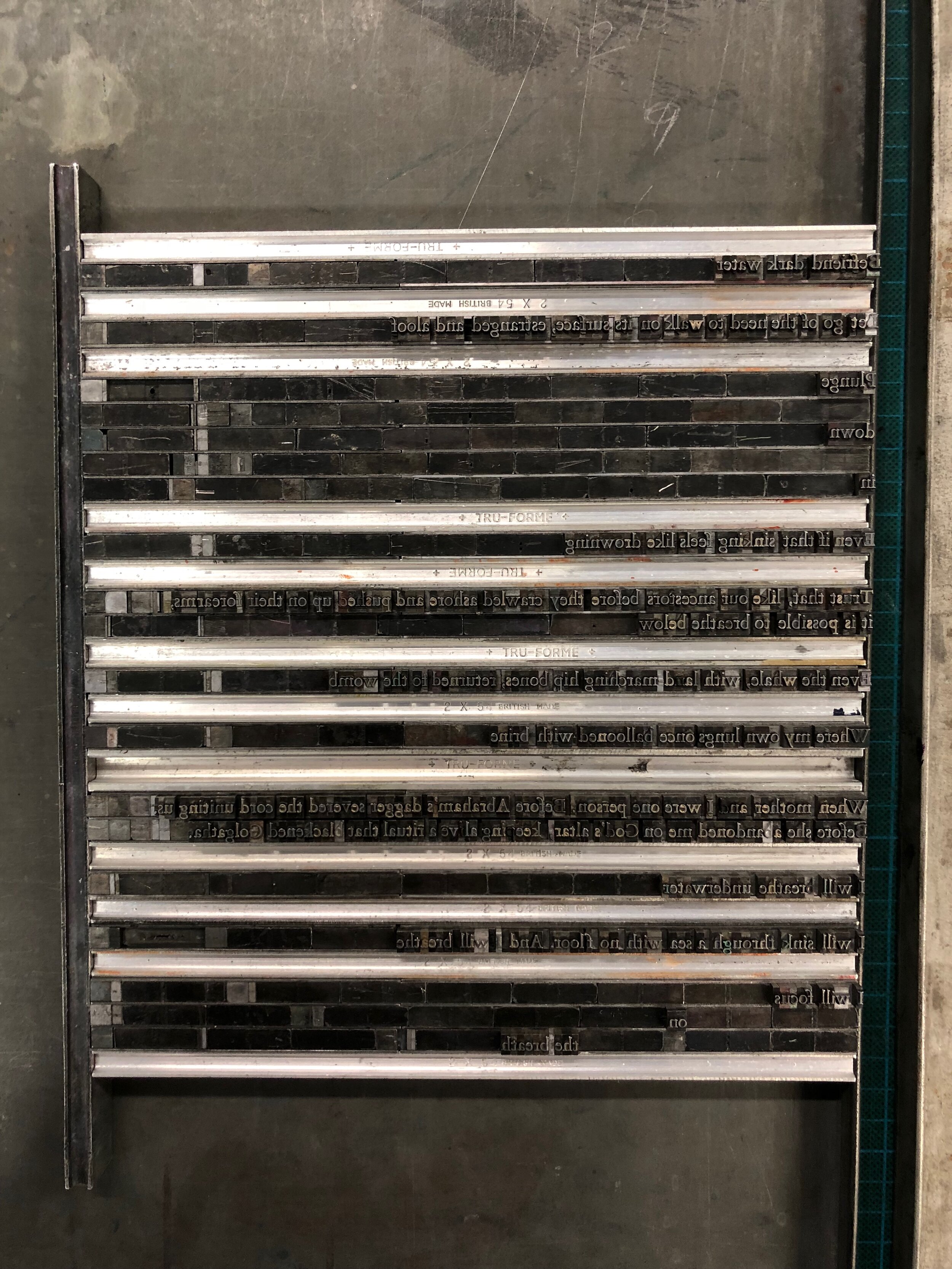

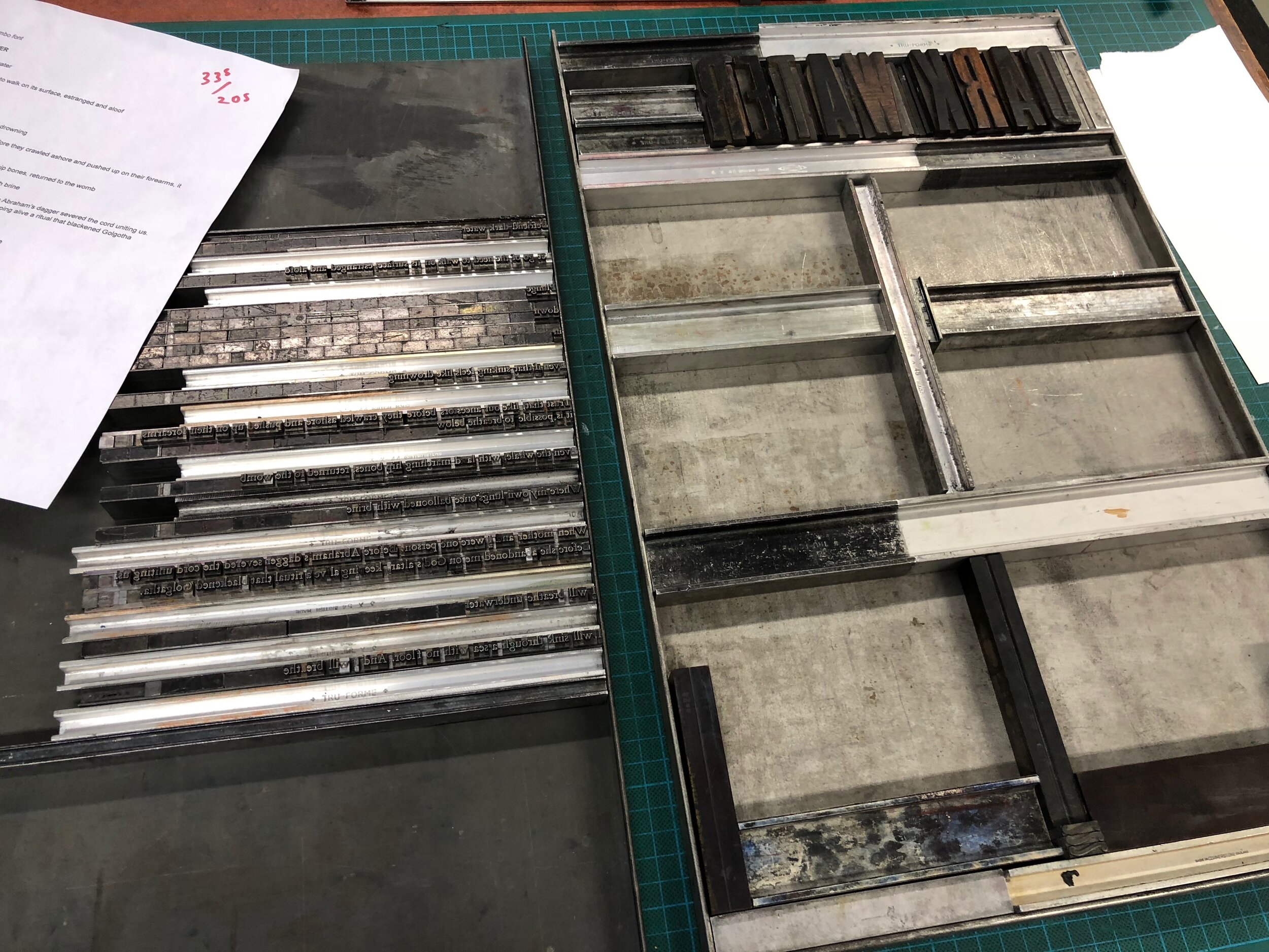

Every aspect of letterpress printing is slower, heavier, more laboured. Every mistake requires a surgical intervention to correct. The process of repairing a typo perfectly resembles surgery. The workshop instructor takes a pair of tweezers and tenderly extracts the leaden “d” from the typeset block that was meant to be a “b”. It can be confusing since the metal slivers of type appear in mirror image and backward. The phrase “mind your p’s and q’s” originates from this very confusion.

You have to work for each word. Fishing each letter out of a drawer segmented into compartments of various sizes. A large rectangle full of e’s, a smaller one for the less frequent x’s. You reach the end of each sentence feeling like a marathon runner passing a mile marker. If talk is now cheap, so is type. This was not always so. Our instructor informs us that apprentice typesetters had money withheld from their pay for any mistakes. They learned to be careful even as they learned to be swift.

Even though the behemoth of a machine that creates our day 1 print project is all but extinct – few print engineers remain who can service such a device – it also seems somehow indestructible, immortal. I get to turn the crank and make a print. You walk several steps beside the machine as you rotate the crank. You feel the lumbering inertia. Heavy gears turning, dragging the paper across the typeset chunks anchored into place with magnets and lengths of metal. So much exertion for a single print.

Yet it is this very exertion that makes each print feel earned. Created from ink but in some respect a donation of blood for every ink-stained page. Set aside to dry overnight in metal racks. The ordeal of childbirth to help us cherish our new arrival.

Pain to italicise the sense of reward.